Themes present in the work of Jean Paul Riopelle

The projects are based on one or more of the following themes related to Riopelle and his work, which is still relevant in the Canadian socio-cultural reality:

– Ode to Nature: art and the environment

– Autochthony: art, history and identity

– Migration: art, here and elsewhere

○ The project has a clear artistic dimension;

○ The project includes an artistic mediation dimension, particularly around the work and life of Jean Paul Riopelle;

○ The project plans to offer a creative legacy, notably but not exclusively, in the public space.

“It’s been said that nature was always present in my work. It’s because I always go toward nature, or at least I hope I did, rather than come from nature.”– Philippe Briet. Excerpt from an interview published in the exhibition catalogue for Riopelle, Peintures, estampes, Musée des beaux-arts et Hôtel d’Escoville, Caen, May 12 – July 15, 1984. S.p.

Nature is everything that surrounds us that hasn’t been built or modified by humans.

This would include forests, waters, animals, etc. While we often think of nature as existing outside our inhabited environments, it can also be found in our cities and towns—like the neighbourhood squirrels living among us.

Nature is both fragile and forceful. It is the tiny plant reborn each spring and the raging sea that washes away everything before it. Above all, nature fascinates us with its complexity and its beauty. How could we ever remain unmoved before the spider’s delicate web or the seasons’ ever-changing palette of colours?

A love of nature was instilled in Jean Paul during his early years. As his scout leader noted, “He has a passionate love for scouting and nature.” We know that he would often go canoeing and fishing as a boy. He also spent the long days of summer out painting

in nature with his art teacher. In the city, they would paint still lifes, work which Jean Paul approached in his usual playful manner, giving one of his pieces the title Nature bien morte (Very Still Life)! One of his very first works is called Hibou premier (Owl the First). His love for birds will be a recurring theme in his paintings.

In his twenties, he went on vacation with his parents to Saint-Fabien-sur-Mer, in Québec, where he did numerous paintings depicting the nature found in this region of the Bas-Saint-Laurent.

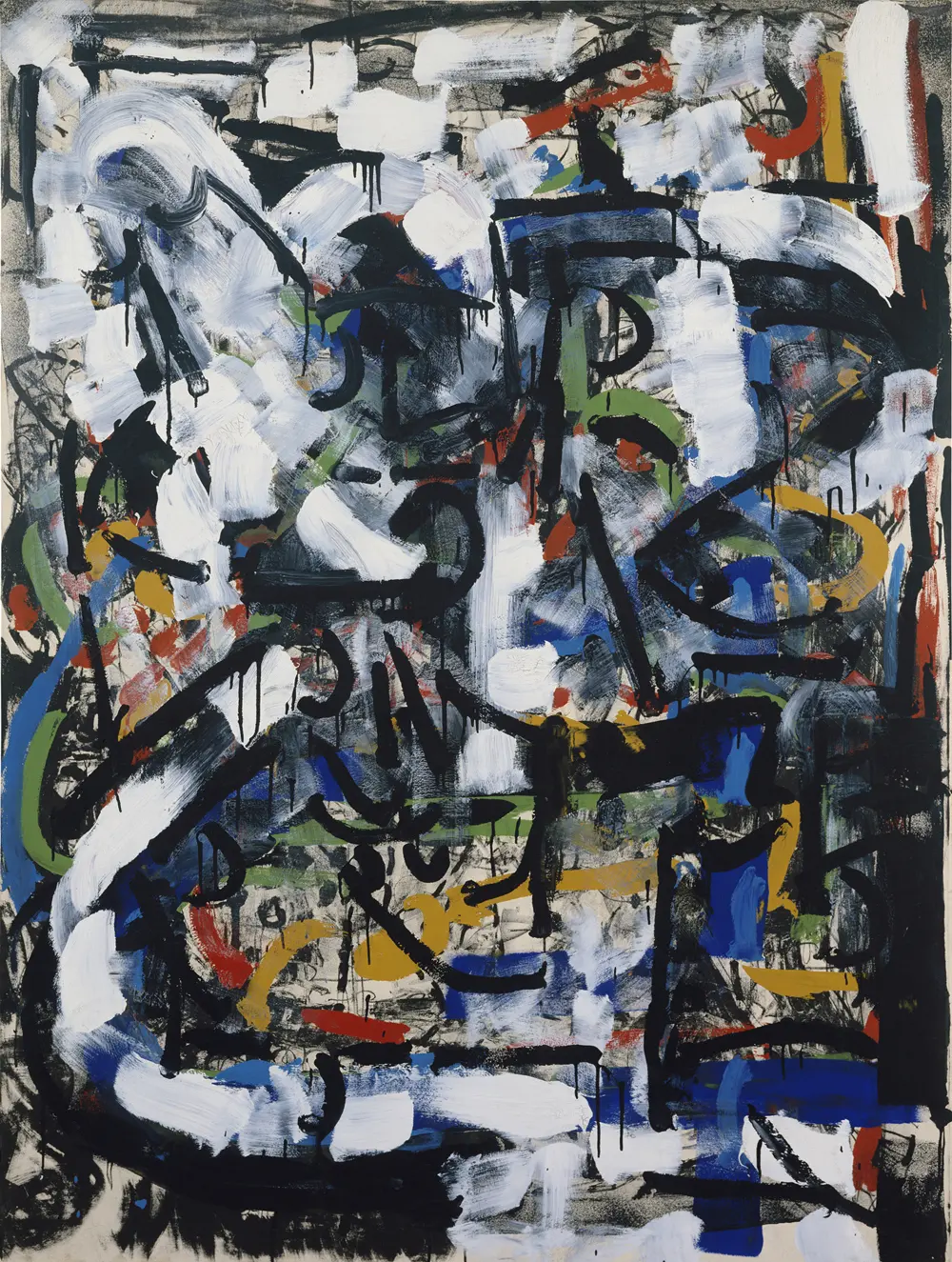

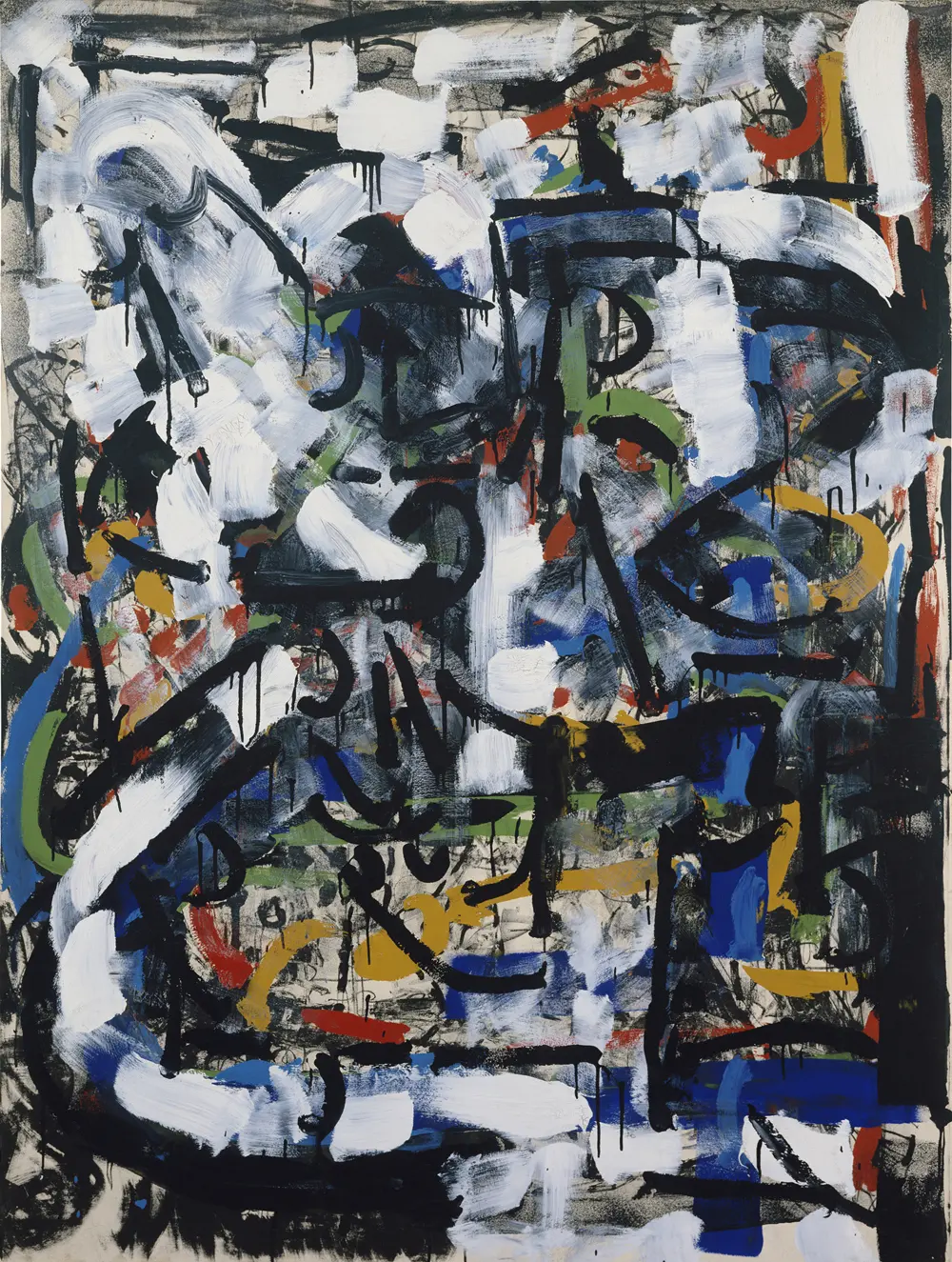

In the 1950s and 60s, at the time of his large abstract paintings, Jean Paul’s connection to nature did not waver; in his colourful mosaics, it is nature that is bursting out. He also continued his regular excursions into nature while living in France, first in Vétheuil and then in Saint-Cyr-en-Arthies. He went fishing and hunted wild boars.

Beginning in the 1970s, his work is marked by the hunting and fishing trips he took in Northern Québec: geese, moose, icebergs, leaves and the wind invade his canvases more and more. At the end of his life, Riopelle settled in a beautiful manor on l’Isle-aux-Grues, near the shores of Montmagny. He lived with the rhythm of the white geese. His final work, L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg, completed in 1992, is a testament to his total commitment to nature.

It is there that he died on March 12, 2002.

• 🎬 from Riopelle Studio presenting the THEME OF NATURE IN RIOPELLE’S LIFE

• Browse the works in THE NATURE COLLECTION

There is a widely shared understanding among Indigenous peoples, the original inhabitants of this land, that the Earth does not belong to humans; rather, it is humans who belong to the Earth. For example, many Indigenous nations have a creation story that is similar to this one: One day, a woman who was with child fell from the celestial world. Seeing what was happening, the Great Turtle caught her. With the help of the other animals, the Turtle saved the woman. She then gave birth to the Earth, Mother Earth, who then begat all creatures.

In this myth, the Earth deserves our respect. We do not inhabit the Earth. It is rather the places and territories which inhabit us and leave traces in us. This is something Jean Paul learned early on. As a teenager, his father brought him to a presentation by Archibald Belaney, also called Grey Owl, an English naturalist who had been fascinated with the First Peoples in North America since his youth. After emigrating to Canada as a young man, Belaney settled among the Ojibwa people in northern Ontario, blending in with their community to the point of adopting their identity. In fact, they called him Wa-Sha-Quon-Asin, which means grey owl. A legendary figure, Grey Owl instilled in Riopelle a great interest in Aboriginal art and cultures, as reflected in his important artistic legacy.

Jean Paul’s passion for Indigenous cultures grew even greater while living in France. His surrealist friends were avid collectors of masks created by the Yupik, Kwakwaka’wakw and Tlingit peoples on the Pacific coast of Alaska and British Columbia. Jean Paul grew interested and, as a man of culture, read deeply on the subject. His reading included two texts on Inuit culture: Les jeux de ficelle des Arviligjuarmiut (String Figures of the Arviligjuarmiut), by Guy Mary-Rousselière, and The Last Kings of Thule (The Last Kings of Thule), by Jean Malaurie.

The titles given to many of Riopelle’s works bear witness to his interest for Indigenous lands and languages, such as Micmac (an Algonquian language) and Muscowequan (an Ojibwa First Nation in Western Canada).

MIGRATION: ART, HERE AND ELSEWHERE

“Today, Rosa Malheur is no more, and neither is Rosa Bonheur. All of the Rosas are dead.” – Jean Paul Riopelle

We all have our own trajectories. Our lives are shaped by our identities, where we live and the decisions we make.

There exists a great diversity of trajectories: the migratory trajectory, for example, for the person who leaves his or her family and country; or the survival trajectory, like that of the geese that fly south in winter and return to the north in summer.

Sometimes, choosing a trajectory can be a step toward freedom: like becoming an adult, leaving the family nest, and sailing off into this adventure called life! Whichever path we take, it will contribute to our life’s meaning.

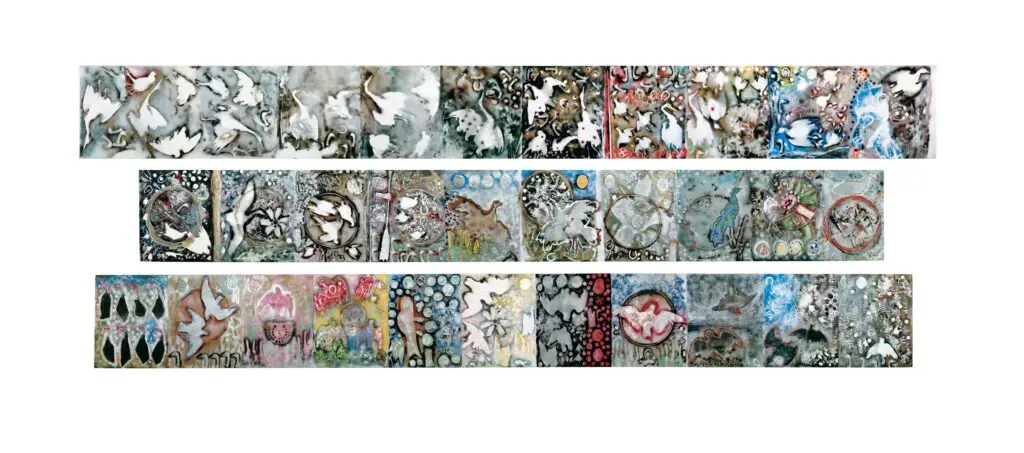

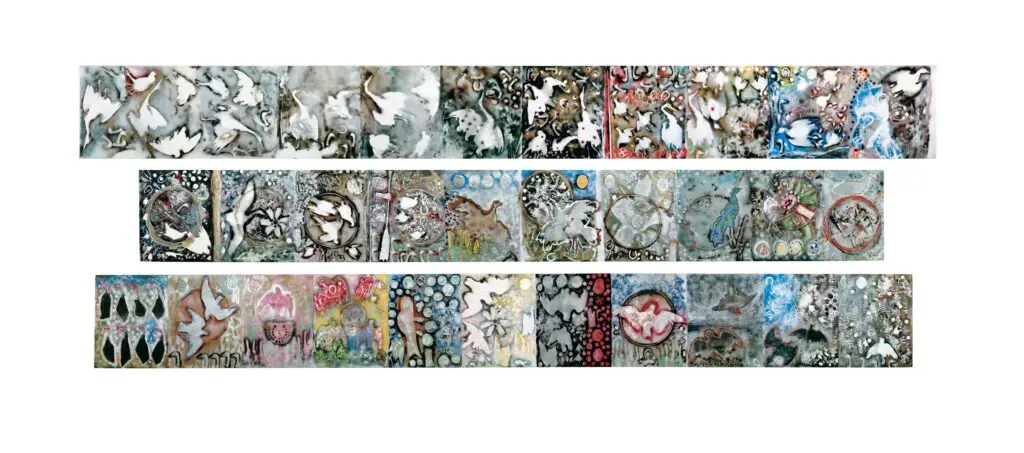

Jean Paul’s life trajectory is fascinating. As a young man, he left for France, where he explored many different painting and sculpting techniques, evolving as an artist. Eventually, he took to the sea on his sailboat, the Serica, and visited many countries; he travelled to the Great North. Like a migratory bird, Jean Paul was always on the move. Then, one day, the journey came to a halt. In 1992, Jean Paul learned t of the death of painter Joan Mitchell, a woman with whom he had shared over 20 years of his life. Propelled by a surge of creativity, Jean Paul took flight one last time: he painted in one go, L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg, an epic work consisting of 30 paintings, a true fresco of his life. Through the objects and animals whose traces he scattered on the canvas, Jean Paul brought to light moments from the past and friends since departed.

What is left after our journeys come to an end? According to an Atikamekw saying, “we go where we’re from—the forest and the universe that surrounds it, Notcimik.” Jean Paul undoubtedly would have agreed with this vision of life after death. He passed away March 12, 2002, in his home on l’Isle-aux-Grues, an island in the middle of the Saint-Lawrence River, on the migratory trajectories of wild geese.